Learning more about the progress of medicine throughout the centuries

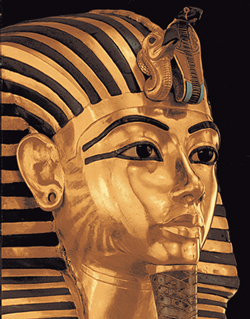

(Modern Medical Technology reveals more about King Tut, Part 1 of 2)

CT (computed tomography) Scan of Tutankhamun gives us more information about his body than previous examinations

In Cairo, Egypt, Farouk Hosni, Minister of Culture, has announced (June, 2005) that the Egyptian team has finished their examination of a non-invasive CT scan of Tutankhamun's mummy. Zahi Hawass, Secretary General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, states that there is no evidence that the young king was murdered.

The scientific team, which reviewed over 17,000 images, was headed by Dr. Hawass, and consisted of radiologists, pathologists, and anatomists under the oversight of Dr. Madiha Khattab, Dean of Medicine at Cairo University.

Dr. Hawass declared that the scientific team confirmed that King Tut died at about the age of 19. His bones, which indicate a slight build, show that he was well-fed and healthy and suffered no major childhood malnutrition or infectious diseases.

In answer to theories that Tutankhamun was murdered, the team found no evidence for a blow to the back of the head, and no other indication of foul play. They also found it extremely unlikely that he suffered an accident in which he crushed his chest.

He also said that some team members interpret a fracture in the left thighbone as evidence for the possibility that Tutankhamun broke his leg badly just before he died; however, this injury alone could not have directly caused the king's death.

The team was also able to rule out pathological causes for the bent spine and elongated skull noted in earlier examinations. The scientists believe the head shape to be a normal variation, and think the bend in the spine is due to the way the embalmers positioned the body.

In addition, the king had a slightly cleft palette and one impacted wisdom tooth. The team noted that extreme care seems to have been taken in preparing the body of the king for burial.

Dr. Hawass said: "The Egyptian team worked on the images for two months. All of us are proud to announce these findings, the first CT examination of a securely identified royal mummy from ancient Egypt. "I believe these results will close the case of Tutankhamun, and the king will not need to be examined again. We should now leave him at rest. I am proud that this work was done, and done well, by a completely Egyptian team."

A few biographical details about Kind Tut

Born about 1341 B.C., most likely in Ankhetaten (present-day Tell el-Amarna), Tutankhamum was first called Tutankhaten, a name that meant "the living image of the Aten", the sole official divinity by the end of the rule of Akhenaten (1353-1335 B.C.).

Although little is known of Tut's childhood British historian Paul Johnson speculates that life in a new capital city, Amarna, must have been insular and claustrophobic. Five or six years before Tut's birth, Akhenaten had created Amarna, in part, perhaps, to escape the bubonic plague that was ravaging Egypt's contested cities.

King Tut's tomb was discovered by Englilsh archaeologist Howard Carter in 1922. Despite the fact that Carter's team had badly mangled the mummy, the scans indicate that Tutankhamun had been in general good health. He may, however, have died of an infection due to a badly broken left thighbone.

Some members of the scanning team maintain that Carter and his excavators fractured the leg while unwrapping the mummy; such a ragged split, had it occurred while Tut was still alive, they argue, would have generated a hemorrhage that would have shown up on the scans.

At any rate, Tut suddenly died about 1323 B.C. and according to the recent computed tomography (CT) scans, he was 18 or 20 years old at the time of his death (judging from bone development and observations that his wisdom teeth had not grown in and his skull had not fully closed).

One theory that appears to have been finally put to rest is that Tut was killed by a blow to the head. A bone fragment detected in his skull during a 1968 X-ray was caused not by a blow, but by the embalmers or by Carter's rough treatment

If Tut had been bludgeoned to death, the scanning report found, the chip would have stuck in the embalming fluids during burial preparations.

Additional details about the CT scan report

On January 5, 2005, the mummy of Tutankhamun (c. 1355-1346 B.C.) was removed from its tomb in the Valley of the Kings for the first time in almost eighty years.

An all-Egyptian team, led by Zahi Hawass, lifted the fragile remains, still resting in the tray of sand in which it had been placed by Carter's team, from their resting place inside the outermost coffin and sarcophagus of the king, and carried them to a state-of-the-art CT scan machine (housed inside a trailer) donated to the Supreme Council of Antiquities by Siemens, Ltd., and the National Geographic Society.

The scan took fifteen minutes and produced over 1,700 images. These images were studied by an Egyptian team, under the auspices of Madiha Khattab, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, and then by a foreign team composed of experts from Italy and Switzerland.

Previous examinations

The mummy of the young king had been essentially dismantled by Carter's team, who were primarily interested in recovering almost 150 jewels, amulets, and other items wrapped with the body and gaining the maximum possible scientific information from the body itself.

In order to remove the objects from the body and the body from the coffin, to which it was stuck fast by the hardened embalming liquids (most likely resins) used to anoint the mummy, Carter's team cut the body into a number of large and small pieces (for example, the trunk was cut in half, the arms and legs were detached).

The head, cemented by the solidified resins to the golden mask, was severed, and removed from the mask with hot knives. Carter placed the mummy back in the tomb in 1926.

The mummy was X-rayed twice since this time, once in 1968 by a team from the University of Liverpool under R.G. Harrison, and once in 1978 by J.E. Harris of the University of Michigan.

The goddess Selket, whose emblem was a scorpion is placed on her head. She is one of four goddesses who stood outside the gilded wooden shrine that housed the chest which contained Tutankhamun's internal mummified body organs.

Selket's outstretched arms represent protection over those she was responsible for. Her divine role was not limited to funerary duties. She was also associated with childbirth and nursing, and she was primarily noted for her control of magic.